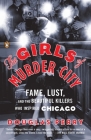

The Girls of Murder City: Fame, Lust, and the Beautiful Killers Who Inspired CHICAGO

Douglas Perry (book page)

Penguin (Non-Classics) (2011), Paperback (ISBN 0143119222 / 9780143119227)

History (20th century), 320 pages (including references)

Source: Publisher (new paperback edition), for review

Reason for Reading: Unputdownables’ Early Reader Group selection

Opening Lines: “The most beautiful women in the city were murderers.

“The radio said so. The newspapers, when they arrived, would surely say worse. Beulah Annan peered through the bars of cell 657 in the women’s quarters of the Cook County Jail. She liked being called beautiful for the entire city to hear. She’d greedily consumed every word said and written about her, cut out and saved the best pictures. She took pride in the coverage. But that was when she was the undisputed ‘prettiest murderess’ in all of Cook County. Now everything had changed.”

Book description, from the publisher’s website: Chicago, 1924.

There was nothing surprising about men turning up dead in the Second City. Life was cheaper than a quart of illicit gin in the gangland capital of the world. But two murders that spring were special – worthy of celebration. So believed Maurine Watkins, a wanna-be playwright and a “girl reporter” for the Chicago Tribune, the city’s “hanging paper.” Newspaperwomen were supposed to write about clubs, cooking and clothes, but the intrepid Miss Watkins, a minister’s daughter from a small town, zeroed in on murderers instead. Looking for subjects to turn into a play, she would make “Stylish Belva” Gaertner and “Beautiful Beulah” Annan – both of whom had brazenly shot down their lovers – the talk of the town. Love-struck men sent flowers to the jail and newly emancipated women sent impassioned letters to the newspapers. Soon more than a dozen women preened and strutted on “Murderesses’ Row” as they awaited trial, desperate for the same attention that was being lavished on Maurine Watkins’s favorites.

In the tradition of Erik Larson’s The Devil in the White City and Karen Abbott’s Sin in the Second City, Douglas Perry vividly captures Jazz Age Chicago and the sensationalized circus atmosphere that gave rise to the concept of the celebrity criminal.

Comments: I am much fonder of the musical Chicago than I probably should be. I’ve never seen it on stage, but the movie version came out at a time when…well, let’s just say that a story about thwarted women who killed their men wasn’t all that far-fetched to me, and I loved “The Cell Block Tango” (still do). I’m not sure when I learned that the show was fact-based, but it was when I read Douglas Perry’s The Girls of Murder City that I discovered just how “ripped from the headlines” – of 1924 – it really is. By the way, the word “Chicago” in the book’s subtitle really is properly offset by quotation marks or a change in font, because it refers to Chicago the show, not Chicago the city; while the “merry murderesses of the Cook County Jail” certainly did captivate the city, I’m not sure how truly inspiring they were. Having said that, Perry’s book is also concerned with another woman – reporter Maurine Watkins, who indeed was inspired to base her first stage play on two of the sensational murder trials she covered for the Chicago Tribune. I think she was pretty inspiring, to be honest.

Perry relies on both contemporary accounts and later works in his exhaustive research for The Girls of Murder City, but the last adjective that describes this work of narrative nonfiction is “dry.” Its primary subject is the consecutive murder trials of “Beautiful Beulah” Annan and “Stylish Belva” Gaertner – the models for Chicago’s Roxie Hart and Velma Kelly – both in court during the spring of 1924 to defend against charges of shooting and killing men who were not their husbands. Both cases were salacious and scandalous, and Chicago’s many newspapers fed the public appetite for news about the glamorous defendants. Women were rarely convicted of murder by Chicago’s all-male juries – especially if they were good-looking women – but following a couple of recent guilty verdicts, there was more at stake for Beulah and Belva.

Within this framework, Perry also delves into the stories of several other Chicago murderesses of the time, the reporters – mostly women, including Watkins – who told those stories to the public, the way things operated and the challenges faced by women at the newspapers where those reporters worked, and the unrestrained climate of Prohibition-era Chicago, where underground jazz clubs flourished and illegal liquor flowed freely. (If you ask me, Prohibition is an object lesson in irony.) He’s got great material to work with, and he crafts it into a page-turner with a firm sense of its time and place. The pace is brisk, and the writing is vivid and occasionally breathless, but Perry succeeds in putting the reader right in the midst of events, including Watkins’ application of her satirical eye to shape them into a hit, prize-winning stage comedy (the musical adaptation came years later).

The environment described in The Girls of Murder City seems to be the birthplace of the celebrity-obsessed, fame-for-its-own-sake mindset we know all too well these days, and it’s fascinating in much the same way. Despite being almost a century old, the story here has a sense of immediacy and a contemporary feel, and its blend of true crime and modern history absolutely held my attention – even without “The Cell Block Tango.”